The Secular And Religious Inside Of Me

I was taught in Sunday school (1954 on) if I committed a sin I should repent and confess to my bishop. I was told that I should fight off temptation, that the natural man was an enemy to God.

At home I never heard my mother talk about sin, repentance, confession or anything about a natural man being an enemy to God. Instead my mother kept telling me that I should either be a piano player or a surgeon. To top it off she said she named me after pianist, Roger Williams, and actor, Alan Ladd.

I ended up taking this outlook into my religious environment. Throughout my church years, I can’t remember using the word sin, unless maybe I was absolutely forced to. In my official service to the church I felt deeply uncomfortable using terms like evil, repentance, and hell.

Without knowing it I was introducing a worldly secular orientation into a conservative tradition of religious beliefs. But, I wasn’t alone. Somehow, the man who became the leader of my religion had a secular inner core too. He read humanistic poetry, dressed in beautiful white suits, had long wavy hair, and chose liberals to come into the church’s hierarchy. I believe that his orientation served as cover for me to feel comfortable in my religious culture.

Another teaching of my religion was that we were to resist temptation in this life to have a more beautiful existence in the life to come.

I never really bought into that. I never heard my mother say that in my home. With good reason, I was raised in Southern California and spent the better portion of my life in a bathing suit. Three hundred and sixty five days of sunshine year round (almost), ocean waves to surf in, swimming pool in my backyard, girls who were as naturally clad as I was. I didn’t see much wrong with this life.

When I watched the Rose Bowl football game every New Year’s Day in seventy degree weather, I would say to myself, “people living in the cold Midwest must be thinking I live in heaven.” Now, when I watch the Rose Bowl game from Utah, I’m convinced of that.

So in my church life I found that I didn’t dwell much on heaven. I liked where I lived. It wasn’t absolutely perfect, but perfect enough.

So when my religion taught me this life was a lone and dreary world, and that our misery would end by going to heaven, I didn’t necessarily think they were talking to me or about where I lived. My thinking was: it’s sunny, let’s water ski, go on a date, dance, and cruise in neat cars.

I honestly didn’t think a lot about the next life. Oh, maybe once, when my eight year old cousin died. I was ten. I felt bad. It was terrible. I was glad my religious leaders said she was in heaven, that she suffered no longer, that she was safe, that she was happy, that she awaited a reunion with her family. What a tough week that was. I openly wept at her funeral. I was devastated as I sat on the front row with her casket open. It was more than I could handle. I ended up on my father’s lap with both of us sobbing.

I was secular and worldly without knowing I was. I wasn’t a misguided kid. I experimented, but what else is there to do when you’re young and live in So Cal.

Not all people flourish in a secular world. At one point neither did I. I floundered my second year of college, not academically, but definitely confidence wise. My supposed acting career took a downturn. That’s when the more conservative side of religion won me over, and gave me a sense of peace amidst my sense of failure and emptiness.

But the net result of this was: I didn’t turn my secular life in for a religious life. Instead, I kind of blended the two. I continued on as a secularly oriented person, but with a sense of gratitude for the spiritual safety net my church provided me in my time of need.

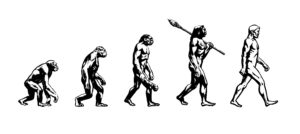

I have enjoyed the enormous benefits of living in a modern society. Evolution answered the profound questions of where I came from. Birth control helped my wife and me from having unwanted pregnancies. The Beach Boys made me feel good about my lifestyle. What was there not to like?

But, church service was a big, big part of that. The church gave me opportunities that I could not have imagined in ten life times.

For example, what more could a white, married, male ask for when he’s a Mormon and is suddenly made a bishop. Your congregation recognizes your authority. You sit up in front of your congregation every Sunday as the presiding authority. Ah, the sweet taste of power.

However, without much time elapsing, that feeling passes away. The position becomes a test of your basic character. For me it came in holding disciplinary courts on members. As a bishop you are expected to keep order in your congregation and purify the flock if necessary. You know the leaders above you want you to be strong and uphold the reputation of the church when members blemish it by their behavior.

For example, a single adult member of my ward came forward and confessed to having extensive sexual activity. This person was known for doing this. Excommunication was expected. The person confessing expected it to happen. My superiors expected me to exercise firmness. But, as I sat and listened closely to this person, I decided to let the matter drop. All I said was, “if it’s forgiveness from the church you’re looking for, you’ve got it. Other than that, if you need help in any way, I’m here for you.”

A few people close to the situation disagreed with my decision. But at the time it didn’t matter. In those moments I had become an advocate, not for the church or the church community, but for that person. I knew I would be seen as too lenient by those whose responsibility it was to assess my judgement, but that didn’t worry me. Whereas, earlier when I first became a bishop, I may have been quick to exercise power; however, as I mellowed in the office, I became more fiercely interested in lifting that person’s burden.

I have often asked myself, what happened in that moment of decision? I concluded, whoever I was at the core, that’s what I was at that moment. That was my fundamental character coming through. And what pray tell was that? It was a kid who grew up wearing shorts, in a near perfect climate, under the hand of a mother who was worldly in the best sense of what that word means, and grateful for a religion that picked me up when I was down.

I was a blend of secular and religious inputs. I hadn’t given up one in favor of the other. I was both. I am both. I would be crazy to turn on the secular world. That’s where I came from. But at the same time, while I’m a lot of things, an ingrate doesn’t happen to be one of them – my religion came along when I was sliding. It picked me up and gave me incredible opportunities.

I do not believe in “either, or . . .” choices. There are many points along the continuum of the secular versus the religious. I’m at some point along that continuum. I’m comfortable with it. There is no war going on inside of me.